How likely would you accept grandma's video game friend request?

Takeaways

Video games are the next cultural phenomenon and virtual reality will lead that revolution

The timing of when you rebalance your investment portfolio could lead to a significant difference in your returns

We're bad at describing probabilities and even worse at combining them

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter, you can subscribe directly here:

Video games killed the sports star

Last week, the popular gaming company Valve announced a new game, Half-Life Alyx. Alyx is a sequel in the Half-Life series, widely considered one of the greatest games of all time. You can check out the 2 min trailer for Alyx here:

Why is this important? You're subscribed to read about tech, finance, and the occasional self-deprecating joke; half of you probably didn't click on the video. Who cares about video games?

Here's why you should care. I believe video games and esports (watching video games for fun) are the next cultural phenomenon. Just like you'll feel left out of conversations if you haven't watched the latest Avengers movie, the day will soon come when you'll feel sidelined because you haven't played or watched the newest video game [1]. I also believe that AR and VR will be the next form factor of how we are entertained, like how the mobile phone, PC, or television has been. I hope that Alyx is the catalyst for taking VR to the mainstream, but acknowledge the market might still be premature.

Sounds ridiculous right? After all, Avengers:End Game alone was a $3bn grossing movie, you can't throw a stone [2] without hitting an unfunny Avengers meme, and Marvel movie spinoffs are reproducing like rabbits. How large could video games be?

Well:

Games are larger than film but still growing quicker. And with the global sports industry at $500bn in size, there's plenty of room for games to grow before reaching the same size as sports.

For games to do so, they'd need to expand beyond kids playing Fortnite on their parent's credit cards. The largest esports tournament already has about the same number of viewers as the Super Bowl, but smaller tournaments cannot compare yet. You'd want new games to be inclusive experiences that adults and even the elderly could appreciate. Would grandma ever play a video game?

Well [3]:

I'm not alone in being bullish on gaming. a16z, a well-known venture capital firm, has increased their interest in gaming, writing about trends they believe in [4]:

Games are the next social network

As cross-platform play becomes the new standard, multiplayer games will grow much faster and larger than older generations

The next big movie franchise, theme park, or toy line will likely come from games.

There are at least three reasons why I'm confident this will happen:

Demographics. Gamer kids are growing into gamer parents. Their kids will be gamers themselves, no longer having to explain why you can't pause a multiplayer game.

Increased inclusion and interaction. Everyone can play video games, even a Saudi prince. You can go from watching a team win to playing that game yourself, right in the same room. When VR finally takes off, you won't even need to worry about complicated controls anymore since the interaction will be intuitive.

Craving for community. Everyone wants to belong to something. Games offer essentially infinite options to identify as part of a larger tribe. As more games realise they are providing a social experience too, developers will start including community features similar to Fortnite's in-game concert [5]

I wonder how the economic model for gaming will change. Selling in-game virtual items for cash is not that old, implying monetisation in games is still immature. On esports, Mitch Lasky, former gaming company exec [6], points out that the current structure of esports is different from live sports. Esports games are directly linked to the publishers, who see esports more of a marketing tool. Esports teams do make money, but only a small share of the overall game revenue. This is in contrast to live sports which get stadium ticketing and TV contract revenue, with teams and players taking a larger share.

Perhaps I'm trying to convince myself the thousands of hours I spent playing video games were not wasted. I doubt it though [7], and think video games and VR are here to stay. I'm predicting with 90% certainty playing video games becomes the norm rather than the exception, and 50% certainty that VR is the platform that enables this shift.

Timing luck and lucky timing

Investors with a diversified portfolio usually rebalance their portfolios regularly, meaning they adjust their investments to get back to their ideal portfolio proportions. For example, if your ideal portfolio is 60% equity and 40% bonds, once a year you might check that ratio and buy and sell as needed to get back to 60% equity and 40% bonds.

Does the timing of when you do this rebalancing matter? This research by Corey Hoffstein claims it does. They define and measure "timing luck" as the difference in performance from choosing a rebalance date e.g. choosing June instead of December. They then construct portfolios with various investment strategies, number of investments, and frequency of rebalancing; I'm omitting the details for brevity [8].

They find that:

Higher turnover strategies have higher timing luck.

Strategies that rebalance more frequently have lower timing luck.

Strategies with a less constrained universe will have higher timing luck.

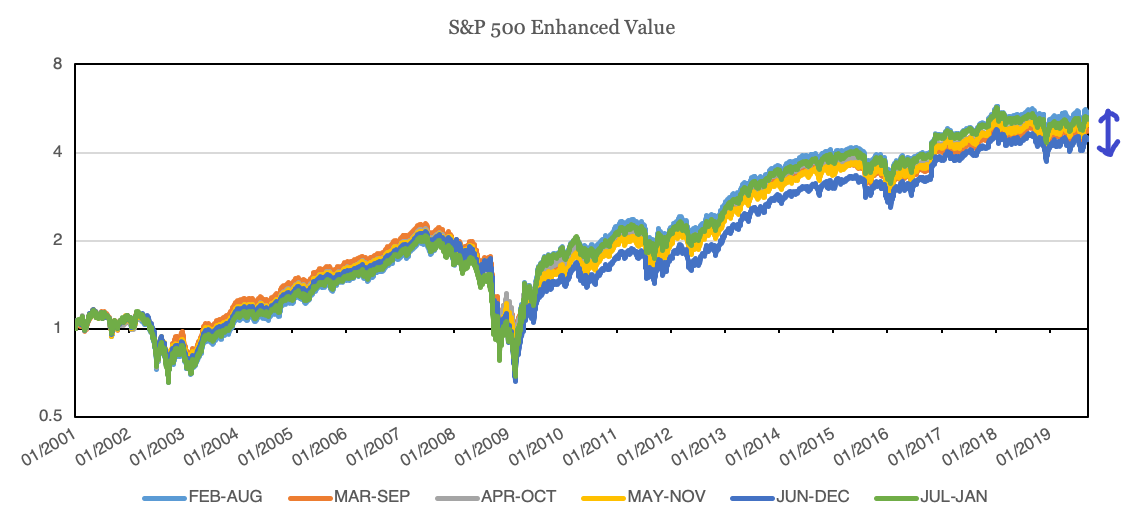

In other words, if you have high turnover, rebalance less frequently, or have less constraints, the greater the impact that rebalancing timing will have on your final returns. The arrow below represents the difference between the best performing and the worst performing variation, of the same portfolio.

They also present a summary table showing that delta across different investment strategies. To understand the below, it's saying that $1 in the "Enhanced Value" portfolio could have returned you from $4.45 to $5.45, and that entire $1 difference is due to luck in when you rebalance.

They conclude by saying:

For reasonably concentrated portfolios (100 stocks) with semi-annual rebalance frequencies (common in many index definitions), annual timing luck ranged from 1-to-4%, which translated to a 95% confidence interval in annual performance dispersion of about +/-1.5% to +/-12.5%.

The sheer magnitude of timing luck calls into question our ability to draw meaningful relative performance conclusions between two strategies.

To put this in context, stocks have averaged a nominal return of ~10% a year. Assuming your portfolio has a similar return [9], up to 4 percentage points of the 10 could be just due to timing your rebalancing date.

One proposed solution for the individual investor is to split your portfolio, though this seems like a lot of work:

we believe that our momentum portfolio should be rebalanced every quarter [...] we proposed splitting our capital across the three portfolios that spanned different three-month rebalance periods (e.g. JAN-APR-JUL-OCT, FEB-MAY-AUG-NOV, MAR-JUN-SEP-DEC). This solution is referred to either as “tranching” or “overlapping portfolios.”

Alternatively, you can reduce the timing luck by reversing the conditions mentioned earlier. Having low turnover, rebalancing more frequently, or having a less concentrated portfolio will all lower the effect that timing will have on the expected spread of returns.

How likely is likely

If I tell you:

An expert says it's likely I quit my job to be Jameela Jamil's exclusive bartender [10]

A second expert also says it's likely

Would you think that it's "likely" or "highly likely" that this occurs?

What if:

The first expert says there's an 80% chance of the above happening

The second expert says there's an 70% chance

What would you think is the probability of this happening now? And would you say that is "likely?" "Highly likely?"

This paper by Celia Gaertig and Robert Mislavsky discusses how people combine probability predictions from multiple sources, by conducting experiments similar to the above. If you've been reading this newsletter for a while, it should not be a surprise that we're inconsistent in our judgement and combination of probabilities [11].

We treat verbal and numerical probabilities differently; organisations and people have differing ideas of how likely "likely" is:

an event described as “likely” in an IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] report must have a 66% to 100% likelihood of occurring. On the other hand, an event described as “likely” in a DNI [US Director of National Intelligence] report must have a 55% to 80% likelihood.

And of course, if you polled your friends on their definition of "likely", you'd get such a wide range of answers it'd be unhelpful.

The paper proposes that:

in general, numeric probabilities are precise but lack direction, whereas verbal probabilities have direction but lack precision

With direction here meaning positive or negative connotations. For example, hearing that an event is "likely" gives me more context and confidence compared to an "80%" prediction.

Having established the difference between numeric and verbal probabilities, the authors study how people combine these probabilities:

we refer to participants using “averaging” or “counting” strategies when combining forecasts,

“averaging” to refer to a combination strategy by which the participant takes a weighted average of the advisors’ forecasts, placing their own forecast in between the advisors’ forecasts

“counting” to refer to a combination strategy by which participants interpret each of the advisors’ forecasts as a positive signal and adjust their own forecasts in the direction of the signal

For example, if received multiple forecasts ranging from 60 to 80%, an "averaging" strategy would get you close to 70%, whereas a "counting" strategy would get you above 80% since so many forecasts confirmed your point of view [12]. If you received multiple forecasts that mostly said an event was "likely", an "averaging" strategy would conclude it was "likely", whereas a "counting" strategy would think the event was "extremely likely" since so many people said it was "likely"

The researchers found that people combined numeric and verbal probabilities differently:

although people average multiple numeric forecasts, they “count” multiple verbal probability forecasts, resulting in forecasts that are more extreme than each advisor’s forecast

In other words, we average out to get to 70% in the example above, but once you convert those numerical predictions to verbal ones, we "count" the number of predictions and get to "extremely likely" instead. The researchers also show that this influences behaviour, and consumers can be influenced to purchase an item depending on how the predictions are presented.

Whether you should "count" or "average" though depends on whether your experts have similar or different information. If they are working off the same information, "averaging" works better at cancelling out idiosyncratic errors. If they are not, then "counting" could be an approximation of a Bayesian strategy that improves your personal forecast.

Shout outs

Modatrova is "a traveling boutique bringing emerging fashion brands to shoppers in private settings". The founder's a friend and looking for women who are tastemakers in their community who would be interested in hosting a private event. Please reach out if you'd be interested to host!

Other

Obvious career mistakes (that might not be so obvious)

Obvious career mistake #1: you mostly ask for general advice

Obvious career mistake #2: you copy the surface, not the cause

Obvious career mistake #3: you plan a route that’s easy, even if it’s not pointed at your destination

What the WSJ got wrong in their investigation of Google's search algorithms

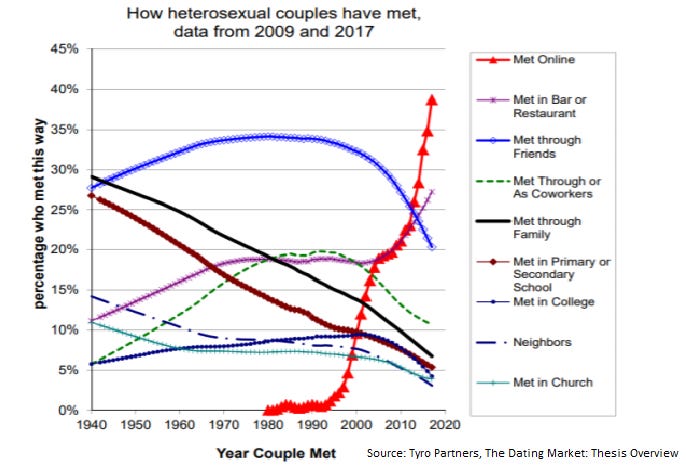

How has the dating market changed?

‘Note in the charts above the up spike in “met in bar or restaurant.” In data science, the technical term for these reporting individuals is “liars.”’

Footnotes

There's already 2.5 billion video gamers, loosely defined, according to Statista. Even if you haircut that number substantially to account for poor statistical methodology, it's still going to be large. Gamers - they live among us. You'll notice I refer to gaming and esports interchangeably, when technically esports are a small fraction of overall video games. I think there's enough ambiguity in definition and that esports will grow enough that the distinction becomes irrelevant.

Heh.

I have an i̶r̶r̶a̶t̶i̶o̶n̶a̶l̶ highly justified strong dislike for Pokemon Go, but acknowledge that it's single handedly converted more elderly into a̶d̶d̶i̶c̶t̶e̶d̶ passionate gamers than any other game I'm aware of

I don't agree with all their trends, particularly the one-off hit point (Games are still one-off hits in expectation) and the organic discovery point (It's just a shifting of advertising channel), but will leave that commentary for another article.

I remain hopeful for some sort of Ready Player One metagame platform that connects all the games you want to play in a VR room, and your status in one game transfers over to another.

Sourced via Blake Robbins

The persuasion of myself, not the wasting of time. It was definitely wasted time.

You can find the details in the paper, and a quick summary is that they made four different portfolios based upon holdings of the S&P 500 from 2000-2019: 1) Value: Sort on earnings yield. 2) Momentum: Sort on prior 12-1 month returns. 3) Low Volatility: Sort on realized 12-month volatility. 4) Quality: Sort on average rank-score of ROE, accruals ratio, and leverage ratio. For each of these 4 portfolios, they further varied the 1) Number of Holdings: 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400 and 2) Frequency of Rebalance: Quarterly, Semi-Annually, and Annually.

A large assumption, of course, but a reasonable one for simplicity. You could argue you're expecting much greater returns than 10%, but so is everyone else and I doubt people actually get them without significantly higher expected risk.

Known for her recent role on the awesome show The Good Place and also for health advocacy. This is a purely hypothetical scenario of course. Unless you happen to be Jameela, in which case please hire me thx it’s extremely likely.

A subtitle to this newsletter could be "How humans are bad at everything we do" but that sounds dramatic.

Of course this depends on the distribution of those predictions and how you weight them, but I'm simplifying for ease of explanation.