Manet and modernity

What's stayed the same and what's changed in art history

Takeaway

Comparing the works of Titian, Dominique-Ingres, and Manet show how artists have influenced each other and rebelled against tradition over time.

Looking at Titian, Ingres, and Manet

December's a convenient time to do reflections. Like prior years, I'll be doing a more comprehensive reflection on the year in the monthly post [1]. I'll spend the weeklies highlighting new topics I've learnt about this year.

First up is art history. I started spending more time learning about art this year, due to a few factors:

Covid cancelled a lot of my hobbies

I've always been curious about art, and believe it still has relevance today

Art is much better when you have context for the piece

I found Smarthistory to be an approachable yet comprehensive website, and have been working through many of the pages. Reading about the intentions behind famous pieces has made understanding the works easier and more enjoyable. For example, finally understanding what Picasso's about in an earlier article I wrote

With that in mind, let's take a look at three pieces with a similar theme, and see how the context of history can give us a better understanding of what the artist was trying to do.

Above we see three reclining nudes, a popular subject for artists for a long time [2]. In clockwise order we have a Titian from the 1500s, a Dominique-Ingres from the early 1800s, and a Manet from later 1800s. All of these artists were famous then, and still are now. "Venus" was fairly uncontroversial during its time, but the other two "La Grande Odalisque" and "Olympia" attracted much more criticism. Why?

To answer that question, it'll be helpful to understand the hierarchy of art genres that people had adhered to for centuries:

For a long time the type of your art would have a certain "rank," and people would automatically judge a painting of still lifes as less important compared to a painting of a religious scene. Not entirely surprising, considering that the church was a big patron of art in historical times.

Let's take a closer look at Venus and the thought that Titian put behind the composition. Venus was probably intended as a marriage gift to the couple for private viewing [3], the hairstyle being typical of brides for that time, and the roses associated with love. Being titled Venus, it was also meant to be a mythological painting, firmly putting it in the top "rank" of art for that time.

To make the painting more interesting visually, Titian's also contrasted the curve of the body, against the straight lines of the background. Also notice how the black lines also direct our attention to the figure. The red lines in the background are not entirely parallel by intention, as this creates perspective for the image and makes it appear more 3D.

Now let's look at Odalisque (which means concubine) and see what's stayed the same and what's changed. The pose is similar, and the use of skin tone on Odalisque and Venus makes them both seem lifelike.

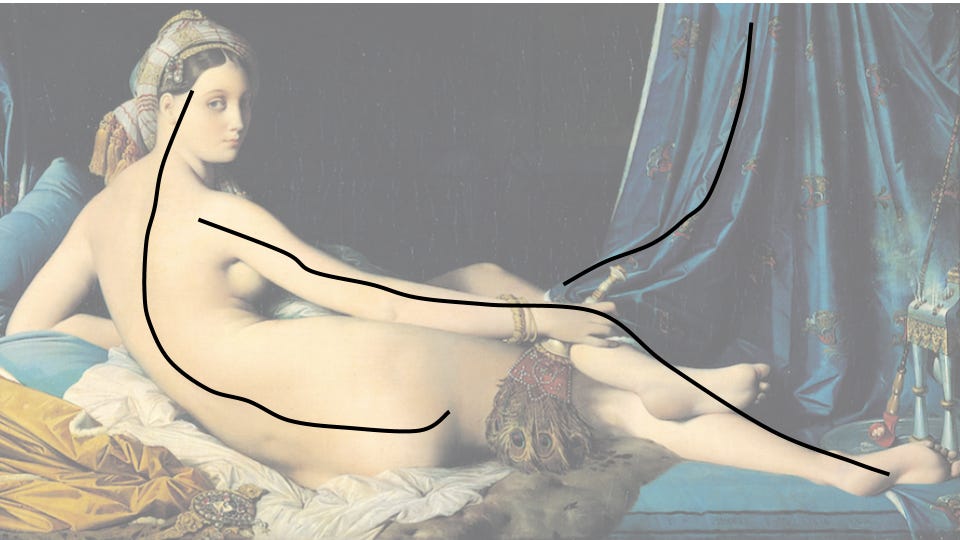

Dominique-Ingres has added more detail to the foreground, such as the peacock feathers or the gems. Also notice that he doesn't use as many straight lines for contrast or perspective. Instead, the painting's all about the curves:

If you stare at the body long enough, you'll also start feeling that something's strange. The body's elongated through the pose, for sure, but doesn't it seem quite a bit too long? The figure's proportions aren't quite right. If you look at the left leg of the figure, you'll also realise that wherever it attaches to in the body is also off. Ingres intentionally did this in order to make the viewer have a heightened sense of the figure's form, vs what might be achievable with "realistic" bodies.

Lastly, Ingres titled the work "La Grande Odalisque," and not after some mythological figure. This would have made the painting "less important," and was his way of making a statement against the rigid hierarchy of art for his time.

Now finally let's look at Manet's work. You can easily see the references to Venus here, from the similar poses, the cushions, and even that vertical line in the background to draw contrast and attention.

At the same time, this is also a very different painting. Most people would say both Venus and Odalisque looked more "finished" and "realistic," whereas Olympia looks incomplete. It's not terrible, but it's also not as "pretty" as the paintings before.

The curves in the figure aren't as long or graceful as Odalisque, and there aren't lines implying 3D perspective, which makes the image seem flat. Whereas Venus was titled after a goddess and Odalisque showed a scene of some fantasy land, Olympia seems very real, very modern.

Indeed, it was that realness that led to "Sticks and umbrellas were brandished in [her] face," and criticism that the painting was “a degraded model picked up I know not where.” Just like Ingres before him, Manet's now fully rebelling against tradition, saying that the art hierarchy was nonsense, and that it was the age of the modern world. No longer would art be focused on painting history; it would paint the now.

Manet's work drew influences from the past, but also rejected many core aspects, scandalising the art world. As a result though, he influenced entire movements, and is now known as one of the first truly modern artists, inspiring impressionism, realism, and more.

I titled the post on Manet, but it's really about art in general. Art's a constantly evolving area, and what was once popular can fade in popularity before being revived again. I've found that understanding the history behind why artists made the decisions they did, to be helpful in better appreciating different pieces and drawing parallels across time periods. If nothing else, it's made me more open-minded.

Footnotes

For last year's reflection and template, see here

One wonders why.

"The subject of the sleeping Venus was central to epithalamia (songs or poems celebrating marriage) popular in Greek and Roman antiquity, and revived in Renaissance Italy." from Smarthistory