There's more to communities than Facebook goat groups

Looking into the common theme of community vs individuality for events, newsletters, and investing

Takeaways

Virtual events and groups should aim to build community by increasing interaction opportunities. If you aren't in a community or building one, you're probably missing out.

Newsletters have trended due to cost, convenience, and control. I share a financial model which you can play with to frame the economics of the business

Individuals are becoming more important for private market investing, both as solo capitalists and as small checks in syndicates

Note: Total est. reading time is ~25min. The first section is ~10min, the second is ~7min, and the third ~3min.

Also: I’m on a speaker panel this month discussing the future of media, see the bottom of this post for details.

I used to travel to Toronto for work.

There was a restaurant I liked to visit, with excellent food, drinks, and staff [1]. I'd half hoped to become a regular there, tasting every item on the menu and swapping cocktail chit chat with the bartenders.

No more.

I used to host cocktail nights.

I'd invite guests to my apartment while I served drinks. Sometimes we even did cocktail lessons. It'd turned into a sustainable, recurring affair where I could catch up with old friends or make new ones.

No more.

I used to do monthly group dinners.

We'd pick a restaurant in Manhattan, reserve a date weeks in advance, and then share food and stories. Group dinners are great; they mean more meals to try.

I've been lucky this year, all things considered. I'm still alive, still healthy, still have a job. No major losses.

And yet, there is this foreboding feeling something has disappeared.

I don't think it's just me either. I'm seeing more posts about people feeling listless these days. That gym buddy you've never spoken to but always comes at the same time you do, the bartender you thought was flirting with you but is just being friendly, or the friend that you're ok talking to once a quarter but no more than that; turns out they all contributed in some small way to the sense of community you felt in your city.

That's gone for now, and people have reacted in different ways. Some search for community via virtual avenues, others are trying to go without. It's never been easier to find others, and also never been easier to be alone.

Today I want to explore that theme, of community and individuality, from a few different angles. We'll first look at the events and groups that have adapted for the individual seeking community. Then, we'll look at the rise of the individual in media, particularly the newsletter business. We'll end off with an overview of the individual in investing, particularly solo venture capitalists [2].

1. Virtual events and groups should aim to build communities

Est reading time: 10 min

Virtual events and groups are not new. This article from 2009 discusses how:

The struggling economy that has forced many companies to reduce their travel budgets and an increased focus on being "green" [...] have converged to make virtual shows a realistic endeavor for the conference business.

And most of us are familiar with MSN messenger, online forums, and social media today, all of which are ways people found each other online.

While the main ideas themselves aren't new, technology improvements and changing social norms have led to enhanced execution of the concepts. Let's first see how events have adapted, and then look into groups.

Virtual events as interactive activities

If you're like me, your current days probably are a mix of working from home, sleeping at home, and finding something to entertain yourself at home that doesn't involve re-binging all 7 seasons of Buffy the Vampire Slayer [3].

I've attended, volunteered at, and hosted a bunch of different virtual events in the past few months. Most have been mundane, a few have been exceptional. Here are my highlights:

Many event organisers seem to believe that all you have to do is just convert all your event sessions to a zoom call. Email out a calendar invite link, play a few minutes of "can you grant me host powers so I can share my screen," and have the speaker talk as though it were an in person event. This works alright, but I find it to be the bare minimum of what we should expect in 2020.

One simple and high value-add to events is to allow for audience Q&A. It's a convenient way to increase interaction during your event and make it more effective. It also means there's a real difference between attending the event live vs watching a replay.

Most organisers have understood this by now, though time allocated for Q&A can still be on the shorter side. I'd advocate for about half the time of your speaking event to be dedicated to Q&A, especially if the purpose of your event is to build a relationship with the audience [4].

Another value-add is to include the materials presented. You can do this before or after the session, depending on whether you want to have the element of surprise. So many events I've attended just send me replay links of the video.

That's good, and we can do better. If I want to cite your expertise later on, it's more convenient to link to static rather than dynamic material, since it takes more time to parse through video content. Since it's essentially free and easy to do so, save your audience's time by also sending the slides.

The other ideas I've seen are more situational.

If you have a small group and want to facilitate people connecting one on one, I've found Icebreaker great for that use case. Icebreaker gathers everyone in a main room, before randomly splitting people up into 1x1 chats. The 1x1s also have guided prompts, in case people don't know what to talk about. After 5 min, the chats automatically end, and everyone's sent back to the main room. You can repeat this as many times as you want.

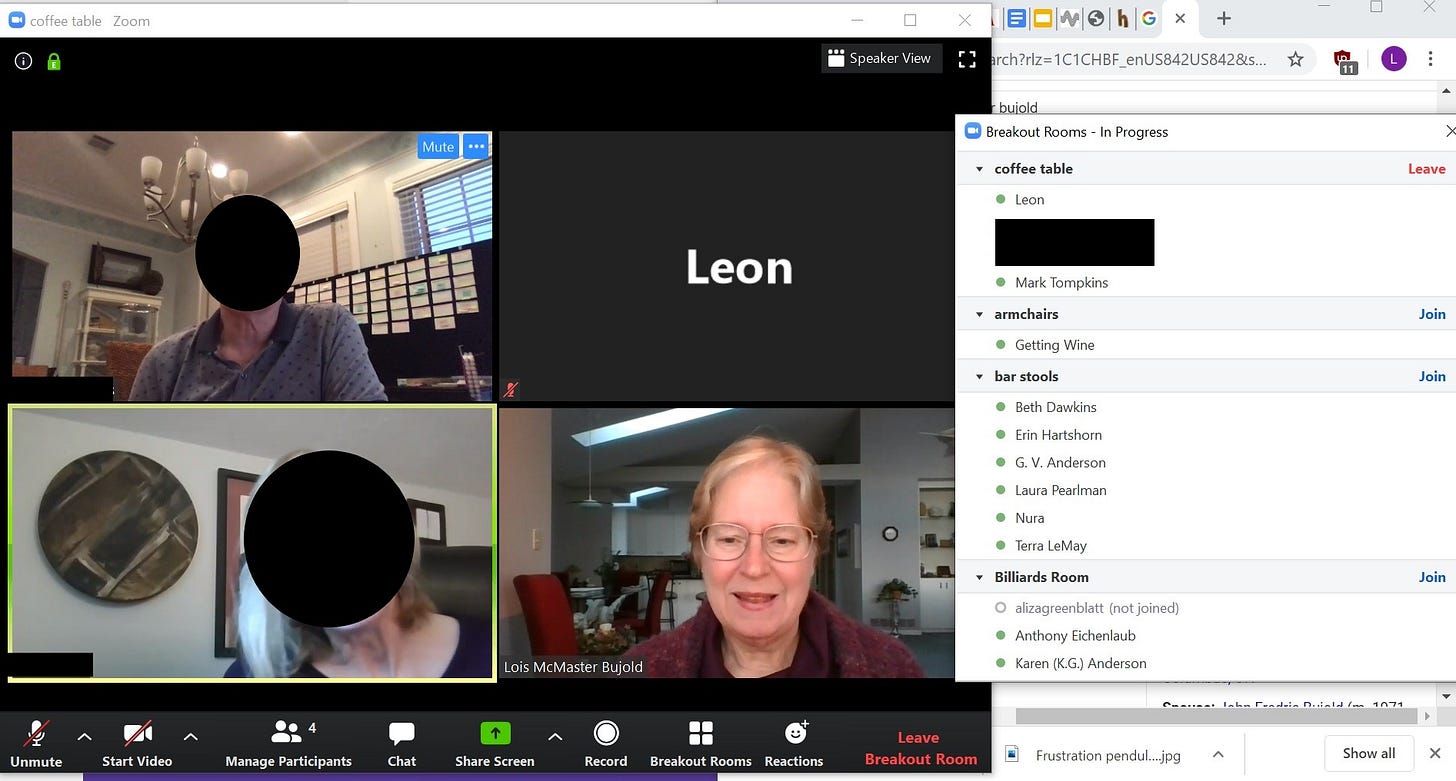

If you have a large group and still want people to interact on their own, you might want to follow what the 2020 Nebula Awards did. The Nebulas are one of the most prestigious Sci Fi awards, and this year did their entire conference online. They hosted an enormous amount of zoom breakout rooms with different sizes, from a single link. They then gave every attendee co-host powers so that the attendees could move around the breakout rooms and join whatever they felt was interesting. Besides having a main speaker room, they had random rooms such as a bar with a bartender teaching recipes, a writing room, and a puppy live stream. Below you can see me in a breakout room with famous scifi author Lois Bujold (I've blacked out the other people for privacy).

A more experimental idea that I had mixed feelings on was Online Town, which the Long Now Foundation tried after one of their seminars. In Online Town, you're represented by an avatar on the screen, and you can walk around a room just like you'd walk around in real life. The conversations that you can listen to are based on proximity, further simulating reality. I found the idea interesting, and it requires much higher user education, for a more unique experience

So far we've covered "work" related events, but entertainers have adapted virtually as well.

For example, I watched an Ellie Goulding live virtual concert recently. She held it at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, putting on a fantastic show that moved about in the museum. The production quality was awesome, and it got great feedback on social media.

Another example is Tomorrowland, the premier DJ festival. They also turned up the production quality, creating visual experiences that concertgoers could enjoy while listening to their DJs play their set live. I didn't attend, but a person who did said she enjoyed it.

However, I think we can do even better. Ellie's concert was excellent, and Tomorrowland seems fun, but both lacked engagement with fans [5]. If you're having a live event, you should make the most of it. Digital experiences simplify communication, and I'd advocate that entertainment events should aim for interaction, just like the "professional" events above. If all your live event has going for it is high production value, I might as well just watch the replay on my own time.

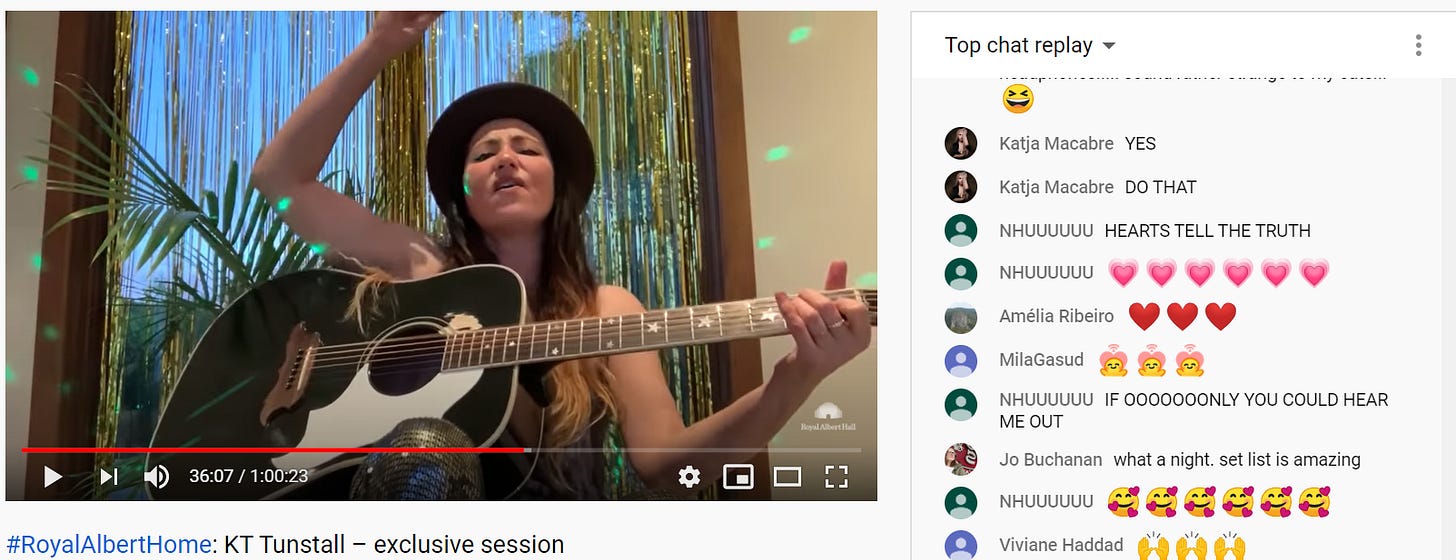

KT Tunstall exemplified this in her live session with the Royal Albert Hall. You can see the lower production quality compared to the two examples above, but what really made the difference was the live chat. It allowed fans to interact both with each other and with her, making for a special intimate session. Live streaming has become... mainstream.

If you don't believe that's sustainable at scale, then take a look at what KPop groups such as Super Junior are doing (h/t Gabriel Tan). They've re-imagined the concert experience, and specifically plan for fan interaction in the concert. It's so much easier to make fans feel special now, and entertainers should learn from this. It's increasingly felt to me that Asian companies are leading the way in innovating on consumer experiences, and this feels like another case study for Western companies [6].

What does this mean for the in person event market? Rafat Ali of Skift believes that this is a watershed moment for the industry, just like what Napster for music. He thinks that 10% of business travel may leave the market permanently, and also estimates that virtual events make about a quarter the amount of revenue that in person ones do, so the market will have to adapt to new economics.

I'm less pessimistic about in person events, and feel that those will re-grow once covid passes. Most business conferences have usually been less about efficiency and more about the networking and taking a paid vacation away from your boss. However, I see events adopting a hybrid model, which could even be incremental to their margins. Sell the in person experience as a luxury, and the virtual experience as a budget substitute. This implies that knowing how to host good virtual events will still be important for the future.

In summary, virtual events should aim for more interaction to build community. It's even easier to do so now, and will result in an even more fanatical following.

Virtual communities as curated clubs

Community building has also risen in importance, both for individuals and companies. For the individual, networking has always been relevant, and virtual groups are an extension of that. For companies, an engaged community implies loyal customers, lowering churn and customer acquisition costs (CAC); the company version of the 1,000 true fans for creators.

On the individual level, the problem with communities is a matter of selectivity. Too selective, and you're not having enough random encounters. Not selective, and you find everything irrelevant. Being a member of a community is a form of signalling, and how strong or weak that signal is depends on how cool your club is.

For example, your MSN contacts were too selective of a group, whereas Facebook groups are not selective enough. Business schools are all about the brand value implied by selectivity. Reddit's light moderation results in some amount of selectivity. On average you get more professional value from your school network compared to your close friend Sunday brunch group, or more informative value from Reddit threads compared to your 180,000 member Facebook group about genuinely stoked goats you don't even remember joining [7].

We're seeing curated communities grow in popularity as an attempt at solving that issue. The goal of such communities is to find that optimal spot on the curve to balance value and selectivity. They usually have some form of admission process to screen their members. When they work, there's a feedback loop where having outstanding members generates more interest in the community, which results in more quality members. Especially when the communities are small, there's an incentive for everyone to make things work, so that you can take pride in your membership.

Some examples of such communities are:

Renaissance Collective which is a community of operators who are "smart generalists"

On Deck which is "where top talent goes to explore what's next"

The Progress Studies slack group for people interested in "the science of progress"

Soho House whose members are "like-minded people with creative souls"

The Interintellect which is "building a new way to be a prolific and successful intellectual in the 21st century"

On the company level, building a community is similar to owning your audience, something we'll come back to later while discussing newsletters and media. It's usually more expensive to acquire a new customer than sell to an existing one, so building a more loyal fanbase directly affects business growth. Gavin Baker elaborates on loyalty here, and the main takeaway is that the avoidance of customer acquisition costs through customer loyalty give your business a competitive advantage.

One industry that understands this well is the gaming market. Look to how the companies behind Minecraft, Fortnite, or Roblox have locked in their target customers. Minecraft has 126mm monthly active users. Fortnite is still breaking attendance records for its in game concerts. Roblox makes >$1bn in rev and is played by half of all children in the US. In many of these games, people are heading there because their friends are there. They're the new MSN of 2020 [8].

Besides value and selectivity, the last factor I'd think about for virtual groups is growth potential. Growth usually comes at the expense of selectivity; as the group grows the value added by the next member is lower on average. For example, when I wrote about Cosign, I was concerned about expansion.

There are ways around this, such as doing batch intakes on a periodic basis. That's the model that colleges, startup accelerators, or online course communities take. Another option is to have a fixed number of spots, and only admit new people once someone leaves. For groups that are intended to be evergreen, such as RenCo or The Interintellect, it'll be interesting to see how they manage growth vs other competing factors.

In summary, groups have been and always will be powerful, though the way they are organised changes with the times. If you're not already building or part of a community, it's worth exploring what's out there. If you are interested in building a community and don't know where to begin, there's also a community for that.

Additionally, to put money where my mouth is, I'm considering setting up a community for Avoid Boring People - I'll be sending a survey next month, but in the meantime let me know if it's something you'd be interested in by replying to this email.

2. Newsletters can be sustainable, lucrative small businesses, but hard to scale

Est reading time: 7 min

In the world of content, individuals are choosing the opportunity to influence and earn by themselves. By going independent, they're giving up some stability and support from the platform, in exchange for higher reward and responsibility. I want to focus on the individual-run email newsletter industry today, although this trend isn't unique to it - youtube, twitch, tiktok, tencent video, onlyfans are all examples of the individual finding success today by unbundling the value of their personal content.

Let's look at:

What's driving the trend of newsletter creation

What the business model and economics could be for a newsletter at scale

What the future of media could look like

Newsletters driven by cost, convenience, and control

Li Jin has written about the passion economy here, proposing that:

Whereas previously, the biggest online labor marketplaces flattened the individuality of workers, new platforms allow anyone to monetize unique skills. […] Users can now build audiences at scale and turn their passions into livelihoods, whether that’s playing video games or producing video content. This has huge implications for entrepreneurship and what we’ll think of as a “job” in the future.

All business models can be simplified as:

Find people

Sell them stuff [9]

When it's costly for a single business to do either of those, you get companies coming in to fill the gap. Call these aggregators, platforms, middlemen, bundlers, distributors, whatever. What they're doing is recognising that there's a need for someone to spread a large fixed cost over a large customer base.

The internet has drastically decreased the cost of both of those tasks, and looks likely to continue doing so. It's possible for someone to find customers and fulfil their orders while keeping a low fixed cost base. Lowering the barrier to entry tautologically means you get more entrants. Increased leverage for all.

Using newsletters as an example, it's easier to get readers now than 20 years ago. I get random reader emails from people in places and life situations that I'd not have imagined (keep them coming!), let alone begin targeting my marketing efforts at. And when I want to send a newsletter issue, I also pay a much lower fee than if everything was in print.

In addition to a decrease in cost, an increase in convenience has also facilitated the newsletter trend. I could be mistaken, but I feel the newsletter boom started picking up after substack announced their funding round. What substack did was make it way easier to get started, as I outlined in an older post. By worrying less about whatever a cname record is and instead being able to start writing immediately, substack enticed many people to try it out.

Another important thing newsletters enable is increased control of your audience; a direct relationship with readers. For now, email is still in this sweet spot where people will open and check the stuff they get. Compare this to snail mail, where half the time I'm getting an ad to sell the apartment I'm renting, or to any feed-based content platform, where half the time I'm seeing something supposedly popular but I don't care about. Owning an audience gives you your own community to care for.

One point of nuance to the above. I said that the cost of acquiring an audience was low, and that the convenience of sending a newsletter is high. However, it is not convenient to acquire an audience. Building a readership base takes work, unless you're Bella Thorne and trying to scam sex workers. Some creators spend more than half their time marketing their work vs actually creating content. That increased friction - of you having to get a reader, and a reader having to give you their email - is what actually deepens the sense of relationship. I signed up for this, therefore it must be good and I should read it. Since you've frontloaded your customer acquisition cost (and effort), selling to that group becomes much easier down the line.

Individual newsletters at scale seem likely to be $300k businesses

Let's split the world of content into 3 main types, since I can't remember more than 3 things at a time:

To entertain

To educate

To engender emotion

If you're a newsletter writer, you're aiming for your own unique mix of the three. Where you end up with influences your pricing. Byrne Hobart has written about newsletter pricing before, and it boils down to: Is this something you can and would expense on a corporate card?

If the newsletter can educate me to be better at my job and earn more [10], you can jack up pricing. If it's more for personal entertainment or emotion, it's harder to do so. I could try, but it's a near impossibility for me to make you feel the same way after reading my writing vs after watching Arrival.

What is a reasonable ceiling for how much a newsletter can make? This post by Andreas Stegmann guesstimates that Ben Thompson of Stratechery makes about $3mm yearly. For lack of better info, I'll use that as the upper bound of what best in class newsletters do [11].

That sounds like a lot, but think about that again. Being among the best in the world only puts you in the million dollar range. Compare this to being the best in the world at a sport, where the top athletes earn ~$100mm yearly. Or being the best in the world at running a business, where your earnings are measured in the billions. If you want highest possible upside, writing a newsletter is not the way to go.

However, if you're ok with running a small-sized business, newsletter writing could be a reliable option. I've made a 5 year newsletter financial model here that you can play around with to see what the economics could look like. If you do, please make a copy, and don't try to edit the original. h/t to Jacob Donnelly and Josh Constine for input on the model.

The model's highly sensitive to the assumptions, which are listed in the sheet and I'll briefly cover in this footnote [12]. It's currently assuming a subscription plus ads business model, but you can change that. It implies that getting a $300k valuation in 5 years is tough but reasonable, which could be something to aim towards for newsletter creators.

Of course, there'll be exceptional creators that earn >$100k yearly, but that requires more aggressive assumptions in the model. $100k yearly is 1000 true fans paying $100 yearly, and at 5-10% free to paid conversion rates, implies you need about 10 to 20k free subscribers. Doable but difficult.

Newsletters might not have many exit options

A recent reddit thread talked about how huge a star Michael Jackson was, and how we don't see celebrities like that anymore. The internet's cost deflation has fragmented the world of content, enabling an unimaginable number of new creators. There’s less concentration and more diversification. What's next?

One easy prediction is that of the supporting industry for all this content. For newsletters, look to paid courses (h/t Cherie Hu), support groups, and more people advising on how to get started.

Another easy prediction is of individual creators bundling. For newsletters, Nathan Baschez and Dan Shipper put together the Everything Substack bundle, and it makes economic sense for others to follow suit. You might not just bundle newsletters, but other types of media like podcasts or consulting.

I also believe that many creators will build a community, as I mentioned in section 1. This will be harder for newsletters to do, since the dropoff rate from email to another service like Slack is tremendous. They'll also face the same issues of growth vs quality and have to figure out what their priorities are.

I'm unsure about exit opportunities for newsletters. Going public is out of reach for most if not all of them given their size. That implies acquisitions and more rollup bundling is the way to go. However, retaining the author is challenging, and most of the value probably belongs to the author. Given the risk, deal multiples are likely to be on the low side [13]. If you're looking for optionality, a large exit is less likely to be a payday, compared to consulting or other work opportunities that come about as a result of your writing.

3. The rise of the individual in investing

Est reading time: 3 min

Nikhil Basu Trivedi did a post about solo capitalists recently. Given the SEC news about relaxing accredited investor rules, I wanted to briefly go over the increased importance of individuals in investing.

Nikhil points out:

Angel investors have been very important members of the fundraising ecosystem for a long time. But over the last couple of years, there's been an increase in individuals investing not just at the earliest stages of companies, but at the Series A and beyond. These people aren't just investing their own capital, are raising dedicated funds, aren't just participating alongside VC firms and often compete with VCs, and have founders choosing to work with them over VCs

Since the individual can make faster decisions, and is potentially more flexible and focused than a VC firm, there's an opportunity to offer either cheaper or more convenient capital to founders. Given how cheap capital is now and how apparently everyone other than me is making bajillions, it's not a surprise we see more individuals want more leverage in this area.

A VC firm is also a bundle. If you're a founder and choosing to work with one due to the experience or network of a famous individual there, you're probably indifferent between getting your capital from that individual directly, or from the VC firm [14]. At some point, that individual might realise they can make more by unbundling their own value from the firm, and offering it as a separate product. The launch of rolling funds by angellist makes it even easier for them to branch out on their own.

The bear case is that we've seen this play out before in public markets, and many famous investors that have tried to strike it on their own have failed. Bill Gross leaving PIMCO for Janus is an example, and there are probably as many Tiger Cubs that have converted to family offices as Tiger Cubs trying to raise a new fund. As with all things, leverage works both ways, and you get high risk with hopefully high expected reward.

I also wonder if the solo capitalist model can scale. These are investors in private markets, usually on the earlier Series A side. Suppose a solo capitalist is highly successful and gets 10x the capital they have now. What do they do with that? Do they move to later stage firms? If they don't, how many companies can they deploy capital into given there's only one of them managing everything?

Moving away from rich people investing to people trying to be rich by investing, the new SEC rules should allow a large number of small check angel investors. Charles Rubenfeld pointed out that the Series 65 qualifies you to angel invest, and can be taken even if you don't have a sponsoring financial institution. Given that angel investing is half status signalling, the relaxation of the rules likely lead to the rise of many angel syndicates and even cheaper capital for founders.

I'm supportive of the relaxation, coming from the mindset that people are free to lose their money however they want. There can be both social capital and dollar capital benefits to investing in early stage companies. More access then is probably a good thing. As long as everyone investing knows the risks, and enough information is disclosed, I'm for letting people have more options to put their money.

Shoutouts

Myself! I'm on a panel with Polina Marinova of The Profile and Josh Sternberg of The Media Nut at the EllisX Media Conference, discussing how newsletters are creating a media renaissance. Use Leon20 for a discount.

I've had to create step-by-step guides for processes at work before. I tried Scribe recently and it saved me a lot of time by automatically generating the guides based on screen recordings

If you're looking for high-end furniture, my friend started her own wood shop. Check it out here

Other

Math and physics guide to animation, one of my best reads this year

Revenue breakdown of big tech companies. h/t Jing Yong for introducing me to the site Visual Capitalist

Introduction to knot theory using rational tangles. The math required isn't hard, but it takes work to understand the concepts.

Footnotes

Aloette for the curious.

To be clear, I'm not making the case that Covid caused these trends. It may have accelerated some, and had no effect on others. I'm more trying to explore the general theme of community from different interpretations

Having watched this for the first time, I'm surprised by how many of its great episodes still hold up. Also, the Spike/Buffy relationship is really creepy both ways man.

Having Q&A means you'll need to be more effective at moderating, which isn't that big a deal most of the time.

That was the primary reason I didn't get a ticket for Tomorrowland, since I didn't see the value add personally.

For example, tipping or subscribing to live streamers has been a large market for China streamers, and took off later for Western ones

Note that I'm not saying your personal friendships have no value; this is more from a "professional" point of view.

I haven't read either yet, but there's a detailed Matthew Ball piece on gaming here and a Jon Lai one here

Ideally at a profit, though selling stuff for less than it's worth seems to be all the rage these days. You make it up with volume I suppose...

I thought about putting "earn" as the fourth factor, but I'll group it under the larger bucket of education to keep the Whole E Trinity.

h/t Lenny Rachitsky for the article. You could argue that there are many businesses that are newsletter equivalents and earn way more than that. For example, if you think of equity research as an expensive newsletter, the market size is large. I'm sticking to more individual based newsletters for most of my analysis for simplicity.

The model's biggest issue is that it's only 5 years, and then assumes a terminal value after that. If you've done financial modeling before, you know that's a bad idea, since the year 5 and terminal growth rate are going to be very different from each other. The next biggest issue is the terminal value assumption. The implied valuation multiple I get from assuming reasonable terminal growth rates and cost of equity is way too high, given actual acquisition multiples of 3-5x EBITDA. The model has two cases you can toggle, one which assumes you monetise immediately and take a hit on growth, and the other in which you monetise after you've gotten traction. Feel free to double check the model and lmk any errors

h/t Nathan for touching on this in a Highlighter call

This is a huge generalisation, and of course there are many other benefits a VC firm can offer vs an individual.