We wanted Her, instead we got Tinder

The margin trap of AI companies, value investing concepts, and tradeoffs

Takeaways

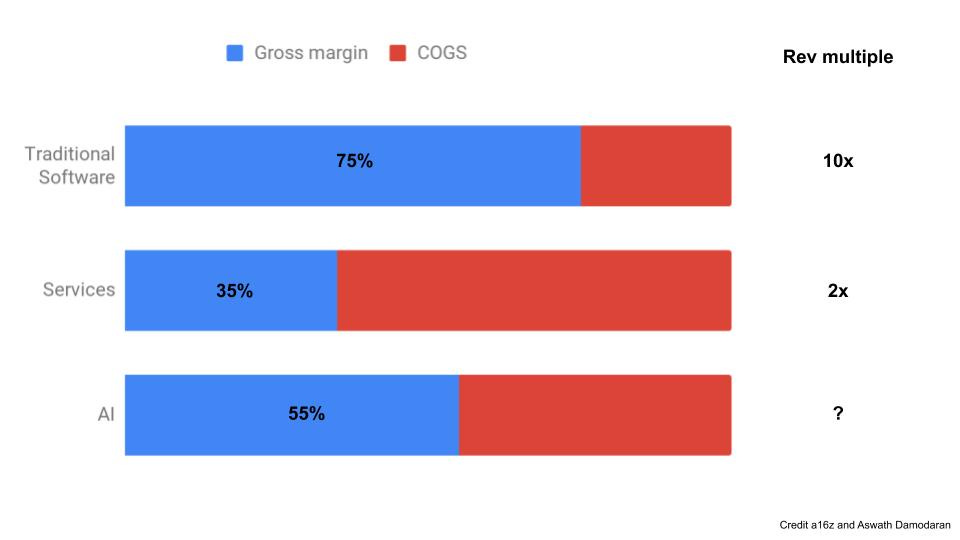

AI companies seem more like services businesses than software businesses, implying they should trade at lower valuations

The only person that Charlie Munger invests in says investing isn't about being smart, but about thinking like an owner

Try to better understand the tradeoffs in decision making

AI as a service(s business)

I've written about machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) before [1], summarising Vicki Boykis' work on how you often don't need fancy tech, and usually the business dictates, not the tech. Scott Locklin elaborates on the problems faced by ML startups here [2], mostly responding to a related a16z post here.

His main points are:

ML costs a lot for marginal payoffs

ML startups generally have no moat or meaningful special sauce

ML startups are mostly services businesses, not software businesses

These are more negative views than consensus, so let's see why he thinks this is the case. I'll be quoting from both Scott and the a16z post by Martin Casado and Matt Bornstein.

Cost

Taken together, these [cloud operation and compute] forces contribute to the 25% or more of revenue that AI companies often spend on cloud resources. In extreme cases, startups tackling particularly complex tasks have actually found manual data processing cheaper than executing a trained [ML] model. - a16z

The pricing structure of “cloud” bullshit is designed to extract maximum blood from people with heavy data or compute requirements. - Scott

Is 25% of rev spent on just cloud operations [3] a lot? To contextualise that number, let's look at the total cost of goods (COGS) of Salesforce, a best-in-class software company. Their 8K shows a total COGS of 25%, which includes all other costs that Salesforce would classify in that category [4], not just cloud costs. In order to have the same margin as a Salesforce, AI companies would need to have no other COGS besides cloud costs.

anecdotal data shows that many companies spend up to 10-15% of revenue on [manual data cleaning and data accuracy maintenance] process – usually not counting core engineering resources – and suggests ongoing development work exceeds typical bug fixes and feature additions - a16z

Turns out AI companies do have other COGS, spending up to 15% on manual data processes. Mainstream media focuses on the predictions from machine learning, but data scientists spend more of their time on data collection and cleaning. That isn't going away, meaning most AI companies are immediately 15% less profitable than a software company. That's also before any other COGS involved, implying final gross margins are even lower.

The allure of investing in software companies is that marginal costs are low, so a high percentage of incremental revenue is converted to profit. AI companies need to lower that COGS % or expect some benefit of scale in order to be as attractive. Is that likely?

the computational power of GPU chips hasn’t exactly been growing apace - Scott

AI requires graphics processing units (GPUs) to do the computing. However, the resources required have grown enormously compared to the growth in computing power; Moore's Law isn't applying on the AI compute side. We shouldn't expect that 25% COGS above to go down significantly any time soon.

Since the range of possible input values is so large, each new customer deployment is likely to generate data that has never been seen before - a16z

most people haven’t figured out that ML oriented processes almost never scale like a simpler application would - Scott

Compare selling Microsoft Office vs selling a consulting offering to a company. In the first case, you can give the same copy of Office that you've been selling to all other companies. In the second, you'll have to create new materials tailored for that client [5], which means you'll always incur incremental costs when getting more revenue.

If AI is more like the second case, this means we shouldn't expect the other 15% (and any other COGS) to go down either. That low margin still takes a lot of work to get. Not only are AI companies less profitable, but we should expect that margin profile to last for a while

Moat

Is that increase in cost worth it? Neither a16z nor Scott seem to think so:

In the AI world, technical differentiation is harder to achieve. [...] Data is the core of an AI system, but it’s often owned by customers, in the public domain, or over time becomes a commodity. - a16z

I know that, from a business perspective, something dumb like Naive Bayes or a linear model might solve the customer’s problem just as well as the latest gigawatt neural net atrocity. [...] People won’t pay a premium over in-house ad-hoc data science solutions unless it represents truly game changing results. - Scott

If a company's product isn't actually significantly better, they have to result to sales and marketing in order to differentiate. This implies even higher costs compared to a typical software company, which is already sales heavy. It does make you wonder whether the hype around machine learning is justified or is used to justify a company's survival.

I'm uncertain what the threshold is for "game changing" though. One of my readers replied after the Vicki Boykis post that implied he considered 10-15% improvement in accuracy significant [6]. I suppose it'll depend on the company.

If the product itself is a commodity, perhaps the total market is large?

Many companies are finding that the minimum viable task for AI models is narrower than they expected. - a16z

but the hockey stick required for VC backing, and the army of Ph.D.s required to make it work doesn’t really mix well with those limited domains, which have a limited market. - Scott

It's commonly thought that you can just throw machine learning at any problem and it'll magically work for that problem and any other similar problems. Unfortunately, for now it seems like many problems won't yet be improved by flinging AI at it. We wanted Her, instead we got Tinder.

If AI has limited use cases, the total addressable market to sell your AI product into is a lot smaller than what you thought it was. Given VCs consider size of market as a key factor for investment, this seems like it'll be a problem when AI companies need to demonstrate growth in the future.

Services businesses vs software businesses

most AI systems today aren’t quite software, in the traditional sense. And AI businesses, as a result, don’t look exactly like software businesses. They involve ongoing human support and material variable costs. They often don’t scale quite as easily as we’d like. And strong defensibility – critical to the “build once / sell many times” software model – doesn’t seem to come for free. - a16z

services companies are not valued like software businesses are. VCs love software businesses; work hard up front to solve a problem, print money forever. That’s why they get the 10-20x revenues valuations. Services companies? Why would you invest in a services company? Their growth is inherently constrained by labor costs and weird addressable market issues. - Scott

Businesses are often valued based on a multiple of some financial metric such as revenue, EBITDA, or net income. Software companies are usually valued at a higher multiple than services companies, due to the reasons mentioned above. Higher gross margins matter, as described by Two Sigma

Both a16z and Scott are implying that an AI company is more similar to a services company and hence should get a lower valuation multiple than a software company. Even if you think they'll get a higher multiple than the 2x revenue that services get, AI companies shouldn't be getting the 10x revenue that traditional software companies do, and that these AI companies previously raised money at.

This will likely be a problem for AI companies that have raised at high valuations and are now finding it hard to raise their next round due to more people realising the above issues. I'd expect, with 60% certainty, that we'll start to see lower valuations than expected for late stage AI company private rounds.

The practice of value investing by Li Lu

Warren Buffett's partner, Charlie Munger, has given money to an outsider to run only once in his life. That outsider is Li Lu of Himalaya Capital.

Founded in 1998, Himalaya is a value investing firm, focused on companies in Asia with an emphasis on China. Typical of that investment style, they look to be long-term owners of quality companies that compound over time [7]. They've historically taken a 0% management fee, and 25% carry after a 6% return hurdle. This is unusual in the investment industry, and demonstrates how confident they are in generating annual returns [8].

Since Li Lu is China focused, there are fewer interviews of him than other famous investors. Graham of Longriver recently translated a 9,000 word speech outlining Li Lu's investment philosophy, which I'll summarise below [9].

Li Lu discussed four basic concepts of value investing, the difference between investing and speculating, circles of competence, investor temperament, and what the average person can do to grow wealth. I found that most of these can be bucketed under his four concepts, which are:

Stocks represent part ownership of a business

The market is a guide, and it's up to you to accept or reject it

Investing is about probability and a margin of safety

Build a circle of competence and stick within it

Stocks represent part ownership

The concept of buying a stock as buying ownership in the company is common among followers of Buffett's value investing style. Rather than viewing a stock as a number, Li Lu views it as a responsibility. This is in contrast to long/short hedge funds who trade more on sentiment and price catalysts, or quant funds that trade on who knows what [10].

no longer were people trying to guess the future results of the East India Company; they were simply trying to guess the behaviour of other people buying and selling the stock.

Li Lu discusses the history of the stock market, which was first created to let companies raise capital to fund their growth. It then took advantage of humanity's gambling nature, to become not just a bet on the future of the company, but a bet on what you think other people think of the future of the company. This is similar to the Keynesian beauty contest concept.

This is the biggest difference between investing and speculating: in the end, the net result of all speculation is zero. Of course, there will be some people who win for a bit longer; and some [who are taken for suckers] without any chance to strike it rich. But with enough time, all speculation ends in a zero-sum result.

Therefore, due to their focus on short term behaviour, speculators have absolutely no influence on economic growth or a company’s profits.

He makes a distinction between investing and speculating, putting people that forecast company performance in the former category as investors, and people that forecast how others react in the latter category as speculators. Investors care about company fundamentals and the long term, speculators care about sentiment and the short term. In his view, most of the investment funds out there now would be classified as speculators.

I'd disagree with Li Lu on speculator influence, and do believe speculators can influence company behaviour, whether it be through activist investing or more regular investor conference meetings. We see companies make decisions all the time that were directly due to shareholder pressure, such as fire CEOs, divest businesses, or sell the company.

This doesn't take away from his general point though, that speculating as he defines it is zero-sum. When you outperform on a company due to issues unrelated to fundamental company growth, someone else on the other side of that trade has underperformed. If you have better returns than the market, someone else is having a worse day.

The market is a guide

For the most part though, you can just ignore him. But when Mr. Market becomes extremely worked up – either excited or depressed – you can use him to buy and sell.

He discusses the popular anecdote of Mr Market, which highlights how the stock market can be viewed as something that shouts a price at you continuously. It's up to you to make a decision on when to buy and sell, and you're better off ignoring the market price most of the time. You're not in a hurry; activity is the enemy.

When you are at school and hear about value investing, you think it should be no big deal to put into practice. But as soon as you get to work, you realise that there are real people on the other side of every transaction. [...] they are superior to you in every way and don’t at all resemble Graham’s Mr. Market.

So after a while, after being continuously scolded by your boss, you will feel that Mr. Market and these people are all better than you. You will start to have doubts.

Value investing is much harder to do in practice, since you do fewer trades. It's one thing to say you're a disciplined person; it's another to resist buying options in your robinhood account when you hear your friends made $10k in one day by lurking on r/wallstreetbets. When everyone around you is making money quickly, it's nearly impossible to stick with a less exciting strategy.

This is easier to do when you adopt the owner's mentality mentioned above. If you bought stocks with the same attitude you did in buying a house, you'd be more diligent and level-headed about when you buy.

Probability and margin of safety

The most important thing in investing is predicting the future but the future is inherently unpredictable. Investing is therefore about probability and a margin of safety.

Investing being about probability is a concept most professionals would agree with, regardless of style. Even the best investors have a hit rate in the 50-60% range, meaning they are wrong a lot [11]. Rather than going in 100% on a single name, they think in terms of investing in a portfolio of names, sizing each position accordingly based on what they think the odds of success for each company is.

The margin of safety concept is not as universal, and more typical of value investors. This is the idea that for every investment you make, you should do so at a price that still gives you enough buffer should there be unexpected declines. If you can find enough margin of safety in an investment, it's worth looking at. If you can't get enough margin of safety, you shouldn't invest.

Circle of competence

Li Lu tells a long story about how he got started in investing after hearing Buffett speak [12]. He started reading more of Buffett's writing, researching companies, and visiting them on site when he could, even when all he could do was talk to the security guard. In doing so, he discovered four lessons in developing a circle of competence:

The first lesson was that stocks represent partial ownership in a business

The second point is that when you start looking at things from an owners’ point of view, your understanding of business will be completely different

When analysts join our company, the first thing we do is to send them to study some companies. We ask them to assume an uncle they’ve never met before has passed away and left them the business. What should they do? They suddenly inherit this asset but have no idea what it is. You must call a board meeting and participate in the discussion. This is the mental model we ask them to use when they conduct their research.

Popularised by Buffett, the idea of a circle of competence is that you should develop a deep understanding of an industry or issue. You should also understand where the limits of your knowledge lie, and not overextend yourself.

These first two lessons are similar to the earlier point about viewing shareholdings as part ownership. Regardless of how large your stake is in the company, Li Lu is saying that you should view yourself as a full owner. That mindset will motivate you to continue wanting to know as much about the company as possible, and understand what decisions are good vs bad for the company's future. Spending so much time on a single name naturally limits the amount of companies you can look at, which will narrow your circle of competence.

The third point is that knowledge is indeed cumulative but you must always maintain intellectual honesty

I've discussed being open-minded and intellectually honest before, and would again agree that this is important but hard to do. When's the last time you've changed your mind on a non-trivial issue?

The last thing is that you should let your passion be your guide. Don’t listen to what others think of you. They have nothing to do with you. Accept that your circle of competence will be small and don’t worry about everything else. Making money doesn’t depend on how much you know; it depends on whether what you know is right or wrong. If what you know is right, you will not lose money.

This is a contrast to how many other investment funds work in practice, where they usually want investment analysts to increase their coverage of names and industry sectors over time. It's hard to tell the limited partners of your fund (the ones that give you their capital for you to invest) that you're not making any changes to the portfolio, and you like the names you're already in. Keep that up long enough and they'll wonder why they're paying you to do nothing. Hence, for many funds there's an incentive to actively trade in and out of names, and the larger the set of names you know the better. This works for some places, and is not Li Lu's style.

Concluding thoughts on value investing

this profession doesn’t demand you to be especially smart, nor to have a high IQ or the best academic credentials

Li Lu describes attributes that make a successful investor, which are:

The person must be independent, and not care about other's evaluations

The person must be objective, and willing to learn always

The person must have both extreme patience and extreme decisiveness when great opportunities come along

The person must be interested in how businesses work

Keeping in mind the core concepts of value investing above, these investor traits make sense. For a typical long/short fund, they'd be less concerned about (3). A typical quant fund would likely be less concerned about (4).

The biggest taboo for investors is to be like Newton and be seduced by the market: to buy at the market’s hottest peak and to sell at its most depressed. If you don’t participate in speculation and stick strictly to investing in what you understand, then you won’t lose money.

The best and most important thing is to have a long enough time over which to compound. Our suggestion to the average person is to only do things you understand and to stay away from everything else.

Given his background as a long term value investor, it's not a surprise that he advocates for growing wealth slowly via compounding over a long term. Not everyone is patient enough to do this though.

Value investing is one way of making money, and there are many other ways that have been successful for various lengths of time. Renaisssance seems to print money, for example, and they do nothing remotely related to the value investing discussed above. If you do decide to stick with value investing, Li Lu's track record speaks for itself. Think like an owner, avoid trading for the sake of it, and know what you're good at.

Tradeoffs

Writing your newsletter post as scheduled on the weekend vs binge watching Peaky Blinders half drunk and then having to stay up late on a weekday [13].

In life, we face tradeoffs all the time.

If someone tells you there's no tradeoff for something, they're either naive, or trying to sell you something. Either way, probably best to avoid them.

Companies run efficiently don't have redundancies. That saves costs, until things break. But neither can you have backups for everything, since it'll be exorbitantly expensive.

Leaving options opens means you have flexibility. That works until you realise you've lived your life with all the options and never settling for something. But neither should you decide on a path without having a backup plan.

In all the important decisions we make, we should:

learn what the explicit and implicit tradeoffs are, and

improve on our process to choose between them

On the first, explicitly writing out what you're giving up, such as with a decision journal, can be helpful. So can doing premortems. The act of fully thinking through the scenario will usually highlight concerns you were only vaguely aware of.

Another way would be to get advice from others, particularly those that have had a similar decision to make in a similar context. They'll be able to flag key concerns or regrets they had. Such advice is highly variable in nature though, and could range from useful to downright harmful. What can be risky for someone might be safe for another.

On the second, it's up to you to decide what framework you want to use. I can talk about optimal stopping theory, game theory, or scenario planning, but most people will find something that works for themselves. As long as you have a framework and keep a record, you should be fine.

Improving in both step 1 and step 2 will lead to better decision making.

I've come to believe that in the short term, it's easier to improve step 1, so I'm working on being able to ramp that process more quickly while maintaining effectiveness. It's harder to improve step 2, which will be a long term project in tracking and evaluating decisions over time. The process of improving both of these steps will also lead you to better understand what you value.

We face tradeoffs all the time, we just don't like to think of them. Unfortunately, forgetting about them doesn't make them disappear. Explicitly laying out what you're giving up in process of an important decision will help reduce regret in the future.

Other

A tale of two talebs. Highly recommend, whether you love or hate Nassim Taleb.

"it is lower-income households that will suffer most from Covid-19, and because they tend to spend most of their income, the hit to their incomes will reduce the consumption share of GDP," Michael Pettis twitter thread on how imbalances in the economy will be resolved

"While Microsoft made $100M it shrunk the [encyclopedia] market by over $600M. For every dollar of revenue Microsoft made, it took away six dollars of revenue from their competitors." Credit Brett Bivens

"Long Bets was founded in 02002 as a way of fostering more accountable predictions about the future." This is the same group that administered the Warren Buffett vs Hedge Fund bet. This post looks at predictions for 2020

p.s. My goal is to help you, well, avoid boring people.

The more I know about what you read and want, the easier I can help you do that.

If you reply to this email with what you’re reading and what you want more of, two things will happen:

I’ll reply with something you might find interesting. And yes, I always reply. Call me out if I don't.

I’ll be able to keep the newsletter relevant for all of you

Looking forward to hearing back!

Footnotes

People would say machine learning is a subset of AI, I'll use the terms interchangeably here for convenience since it seems the principles hold across both areas; Scott would separate them. "The intention of ML is to enable machines to learn by themselves using the provided data and make accurate predictions."

Credit Daniel McCarthy on twitter

The cloud operations here include training the AI model, model inference, data transfer

PDF pg 6 on their FY20 Q4 8K. Also note that for simplicity I've taken wholeco COGS, which includes the less profitable professional services business. If you take the COGS on subscription alone, they're at 80% gross margins.

Or maybe you just find and replace the company name and logos in the deck, who am I to judge.

It was part of a longer reply on striking the balance between tech and business that deserves its own post, and I'll do so in the future. His takeaway was to choose between 3 approaches: 1) Tech can dictate business if it demonstrates improvement on agreed-upon metrics 2) Start less sexy but groom overtime 3) Create a specific space to experiment like Google's 20% rule

"We embrace the value investment principles of Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, and Charles Munger, and today primarily focus on publicly traded companies in Asia, with an emphasis on China. We aim to achieve superior returns by being long-term owners of high quality companies with substantial “economic moat”, great growth potential, and run by trust-worthy people. Some of our holdings date back to our inception twenty years ago."

Most investment firms take a management fee on assets invested with them, and then a performance fee on returns from the assets. A typical fee structure is "2 and 20", meaning a 2% management fee and a 20% performance fee. If you put in $1000 and it grew to $1200, assuming the management fee is taken off ending period values, the management fee would be $24 (2% * $1200) and the performance fee $40 (20% * ($1200 - $1000)). Compare this to Li Lu's fee model which only takes performance fees after the first 6% of returns. Here there would be no management fee, and the performance fee would be $35 (25% * ($1200 - $1000 *1.06)). It's an open secret that many investment firms live off the fixed management fees from growing their assets under management rather than performance. Li Lu's model would be more beneficial for him if he believed he could generate high returns, and less beneficial if he does poorly.

I believe it's the same speech previously translated on gurufocus, and Graham's version seems more comprehensive. I've (very) briefly checked the translation and it seems accurate, but I can't fully guarantee the piece obviously. The original is here

A long/short hedge fund is a popular style of investment fund that goes long (buys) on some companies and hedges that by shorting (selling) other companies. A quantitative fund is another popular style that primarily uses algorithms to make investment decisions. Yes, they probably use ML...

I can't find the source for this stat, and it's known that even the best investors get things right 50-60% of the time. They win by sizing their bets appropriately, and making their winners count

"In the past, my understanding of the stock market was basically that it was full of bad guys. But Mr. Free Lunch [Buffett] wasn’t like them at all. He was very smart and what he said was clever and insightful. I could understand his principles as soon as I heard them. And I felt like what he was doing was something I could do too." Strangely, there’s no mention on Buffett in this 1998 profile of Li Lu, so maybe the story is marketing?

The author would like to stress these are hypothetical, abstract, examples.

Footnote 8: 0.25 x (1200 - 1000 x1.06), or 25% of $140, <$40