Takeaway

Knowing whether a process is ergodic or non-ergodic is critical in knowing how much risk to take. Investing and wealth are non-ergodic processes, which imply that our first thoughts on expected values are very wrong.

I've heard about ergodicity before, but wasn't quite able to understand it until I watched this video by Ergodicity TV. It's an important concept but seems more widely known in physics than in finance. I want to try explaining it in my own words below.

We're familiar with different types of "averages" - mean, median, mode 1. Let's focus on mean for today, and take it as the expected value of some random event 2. How we define expected value can give us dramatically different results, changing our mindset on the attractiveness of bets and how much to bet.

Ergodicity means that the ensemble average is the same as the time average. Something being non-ergodic means the opposite, that the ensemble average is not the time average.

Yeah, I'm not sure what ensemble and time here mean 3 either, so let's look at an example of tossing a coin.

Suppose some random dude tosses a coin 5 times, getting some heads and some tails. We can calculate the time average for this simulation by getting the average number of heads for one person across a period of time. There are 3 heads out of 5 tosses, so that's 0.6 heads (3 divided by 5).

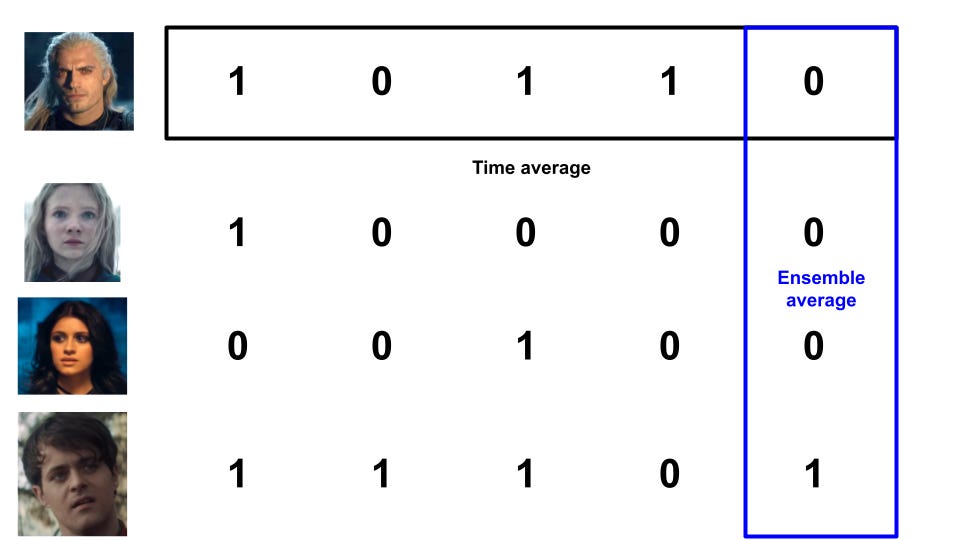

Suppose we get a few more people to toss coins. We get something like below, where I'm representing heads as 1 and tails as 0 for convenience:

There are two types of averages we can use here. The first is the time average from before, where we get the average over some period of time for one person.

The second is the ensemble average, where we get the average over one period of time for multiple people.

The big question that ergodicity tries to answer is: Should we expect these two averages to be the same in the long run?

If we think for a while, we'll be able to reason that we should, in this example. A coin toss is random, and doesn't depend on the previous result. The ensemble average is the same as the time average in the long run. With enough coin flips, we'd expect these averages to be 0.5 4.

That was a lot of words to show something you probably already believed, so why do I think this is so important?

Let's build on the example, by having the people bet on the coin toss. Everyone starts with $1, gets 50% profit if they win, and pays 40% of their bet if they lose. For example:

Rather than the coin toss results themselves, let's think about the wealth that each person will have. If we plot these, should we expect the time average of one person's wealth to be the same as the ensemble average of everyone's wealth in the long run?

Or put another way: would you want to take such a bet if offered repeatedly?

The expected value of such a bet is 50% times $1.50, plus 50% times $0.60, to get $1.05. With a positive expected value, it seems like we should keep betting. Let's simulate some coin tosses to see what happens.

I've coded a simulation of coin tossing in this jupyter notebook 5. Running the above scenario for one person doing 100 coin flips, we notice that their wealth increases to as much as $4, before falling to essentially $0.

Hmm, maybe we got an unlucky scenario. Let's repeat this with 100 people instead, still doing 100 coin flips. I'll also calculate the average wealth (ensemble average) at each coin flip and represent that with a dashed red line 6.

The two graphs below are identical in data; I'm just rescaling with a logarithmic axis for better visualisation.

Something strange is happening. We see one lucky outlier who got to $1k in wealth, and also see that the average wealth (dashed red line) is continuously increasing. However, notice that the majority of these people lost money! In this simulation, 94 out of the 100 people who played ended up with less than the $1 they started with.

If you're not convinced, the notebook has an example with one thousand people; also feel free to adjust the parameters.

What we're seeing is that even though the expected value is positive, and the ensemble average is increasing, the time average for any single person is usually decreasing. The average of the entire "system" increases, but that doesn't mean that the average of a single unit is increasing. Large outliers skew the average, but the majority of people are losing.

This bears repeating. Even when the expected value of such a bet was positive, 94 out of 100 people who played in such a game lose most of their money. Those outcomes happen within the same system, but give you the opposite takeaway on whether you'd want to play.

Wealth in this scenario is non-ergodic, since the wealth in the future depends on the wealth of the past (path dependence). The ensemble average does not equal the time average.

Wealth in general is also non-ergodic, since your investment portfolio's return tomorrow is dependent on the current size and allocation of the portfolio today.

Practically, what this means for investing is:

Be careful about how you're applying expected values, since you want to know if that's the average of the entire system, or what an individual like you should expect on average. If you have probabilities in mind, model them out and see what that implies

What can seem attractive at first is often terrible, as a small number of outlier values skew the average upwards 7.

If you don't like the odds you're seeing, try changing the game. The previous post I did on the Kelly Criterion talks about sizing your bet, which will affect how much you gain or lose.

In summary, ergodicity is about whether the long run average over many simulations is the same as the average over one simulation. When things are non-ergodic, and many things in life are non-ergodic, you have to be extremely careful about the amount of risk you're taking.

Further reading

If you like this post, feel free to share it with others!

Thank you to Tyler Richards, and Recurse Center members Vaibhav Sagar, Sidharth Shanker, SengMing Tan, Alex Yeh for thoughts on this.

Other

"as social media has exploded and more people have entered the game, being technically sound is no longer enough to take home the prize." Welcome to the world of elite flair bartending competition

I might be conflating mean and expected value here, but I think we can simplify for this explanation

Hmm.

50% chance of heads and 50% chance of tails, by definition

Someone should really check my code. Also I think there's a more elegant way of coding it in fewer lines.

This is not the theoretical ensemble average actually, which would be 1.05 to the power of the number of coin flips and increase linearly. Here I'm just doing the average of the actual results, which is why the line doesn't continuously increase (monotonically increase)

Wealth has a floor at $0 but no cap, so the average is unbounded too I think

Interesting observation: If you change the "stake" amount to something more reasonable, like say betting 10% of your current wealth instead of all of it, the results are much better. Also increase the number of flips to 1000 to get a better idea of long-term behavior. Somewhere between 0% and 5% of people lose capital, and the average gain is much higher too.

Really good reminder on path dependence. Thanks!